By Nell Taylor | Special to The SUN

Colorado is holding a water awareness campaign this year, 100 years after the 1922 Colorado River Compact was signed. Pagosa Springs High School Science Teacher Josh Kurz provided the following article as part of Student Water Awareness Week, held April 18-22.

In the spring of 1983, the Glen Canyon Dam was threatened by a massive surplus of snowmelt, so much that there was the danger of the dam overflowing and being destroyed. Now, nearly four decades later, the dam is struggling with the opposite extreme: unprecedented water scarcity.

The Glen Canyon Dam was constructed in 1964, consequently forming the nearly 200-mile-long Lake Powell located in northern Arizona and southern Utah. It provides water for approximately 40 million people and hydropower (through the Glen Canyon Dam) for 5 million people across the southwestern states (California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming) and Mexico. The lake first reached capacity in 1980, but has been dwindling since 1999.

Lake Powell water levels have set a new record low, currently around 3,520 feet, and may reach an elevation where it is completely unable to produce hydropower (3,490 feet) and deadpool elevation, where water cannot be released naturally through the dam’s outlet (3,370 feet), within the next decade.

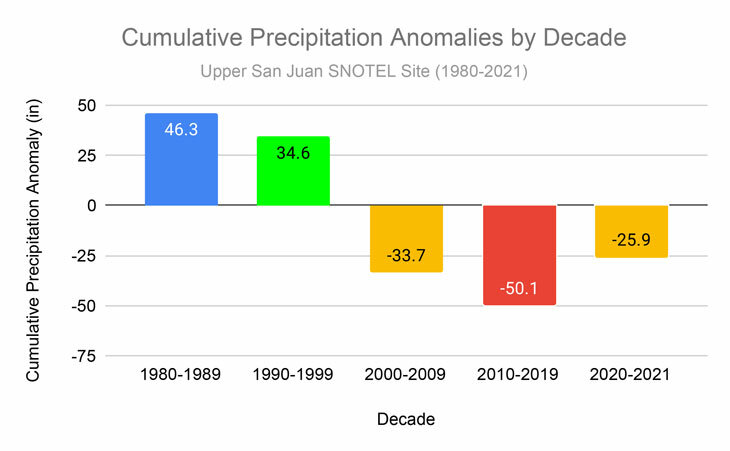

Very recently, the reservoir’s levels dropped into the buffer zone (3,525 feet), meaning the dam cannot operate at full capacity in regard to hydropower production. As a result, the Glen Canyon Dam is now operating at 50 percent capacity, which will lead to higher electricity costs in the southwest area. The primary reason for this problem is that there has been a 20-year-long megadrought affecting the southwestern U.S. area. As shown in Figure 1, it is evident that below-average precipitation years have become more common than above-average precipitation years.

In addition to the lack of precipitation causing the megadrought, there has been exponential population growth in the urban areas that utilize Lake Powell’s water and electricity, which exacerbates the water shortage. For example, the population in Phoenix, Ariz., has nearly doubled since 1999 (the start of the megadrought). Many of these big cities would struggle to exist without the support from Lake Powell and, because the reservoir has subsisted for so long, it has given many people an entitled sense toward its precious resource.

Despite the dam’s illusions, nature ultimately controls our water supply and we will soon be forced to turn to more expensive and less eco-conscious means of getting water in places like Phoenix and Las Vegas. Phoenix is considering funding a desalination plant in Mexico to bring water from the Sea of Cortez, several hundred miles away, costing $1 billion and leaving a massive carbon footprint. Our current water shortage may be analogous to the Ancient Puebloan population of an estimated 50,000 people who once lived in the Four Corners desert, but had to relocate, perhaps because of a water shortage.

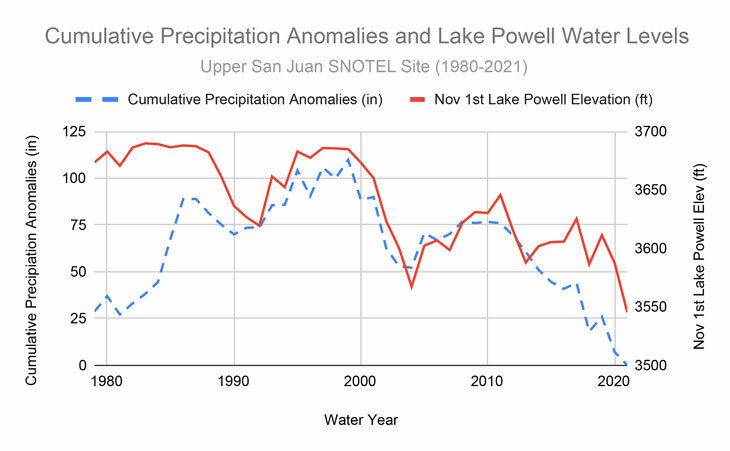

In order to save Lake Powell and allow ourselves to continue living and eating comfortably in the desert, we will need to get out of the megadrought. Before the megadrought will release its grip on our area, we need consistent, above-average precipitation patterns like the 1980s and 1990s, which, looking at Figures 1 and 2, may be unrealistic. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the precipitation anomaly (a running total of the surplus and deficit of precipitation in the upper San Juan area, which is only 0.26 percent of the Lake Powell watershed, but certainly an important contributor) and the Lake Powell levels.

Instead, there will need to be a large cut-back on water usage. This will require much cooperation between all seven states that rely upon the water in Lake Powell, and water restrictions in both the desert communities and the communities that have contact with/control of the Lake Powell water. In the agricultural community, much more efficient irrigation techniques would greatly benefit the situation, as the agriculture industry consumes the majority of the water used from Lake Powell. The most impactful action that a domestic Pagosa household can take is to cut way back on outdoor watering.

Outdoor watering accounts for the largest domestic water use, and by embracing more natural and native yards, we can do our part to save Lake Powell. The greatest lesson we can learn from the Lake Powell situation is that, whether there is too much or too little water, nature is in control, and it is our job to strive to live in harmony with it.